Eli Ping: Eli Ping

To experience a thing as beautiful means: to experience it necessarily wrongly.

– Nietzsche

Eli Ping once got in a bad fight. When he lost his footing, a man got on top of him, intending to drive a knife into his chest. He "could feel that the space between life and death was tissue-thin" and that "what was on the other side was massive."[1] "We live with the closeness of mortality every day," he told me, "but we keep it just outside of our awareness because it's easier... Everything that's not in the realm of the expressed or the visible," he says, "just lives on the other side of that threshold."

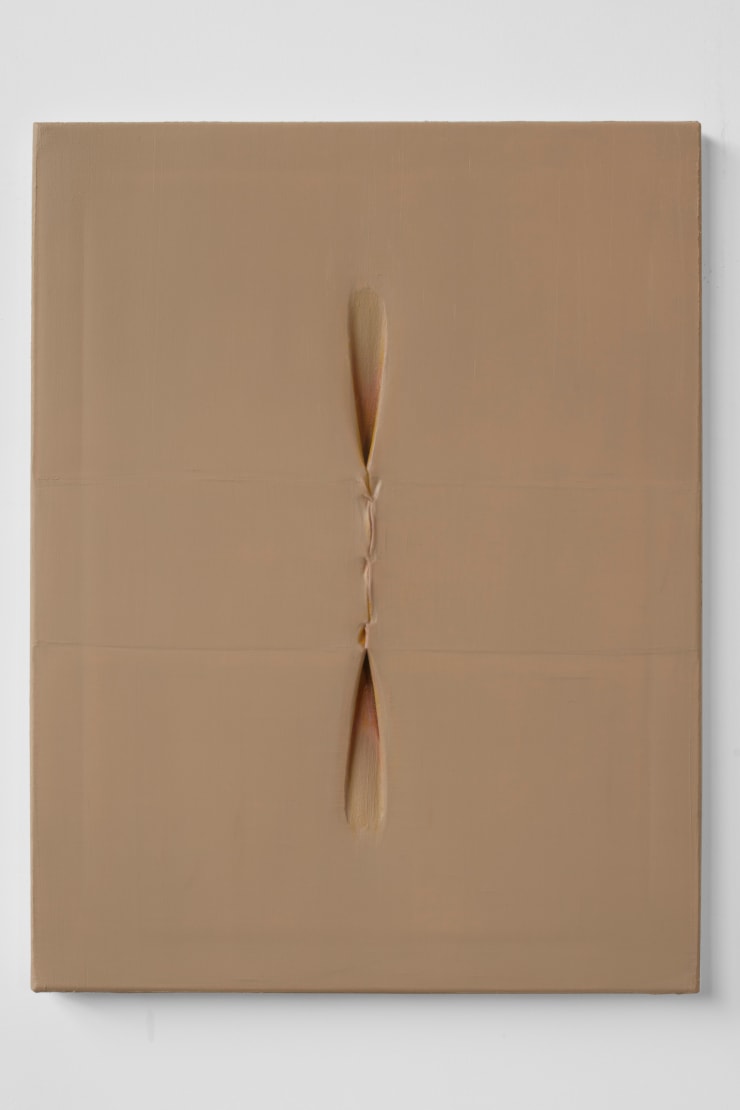

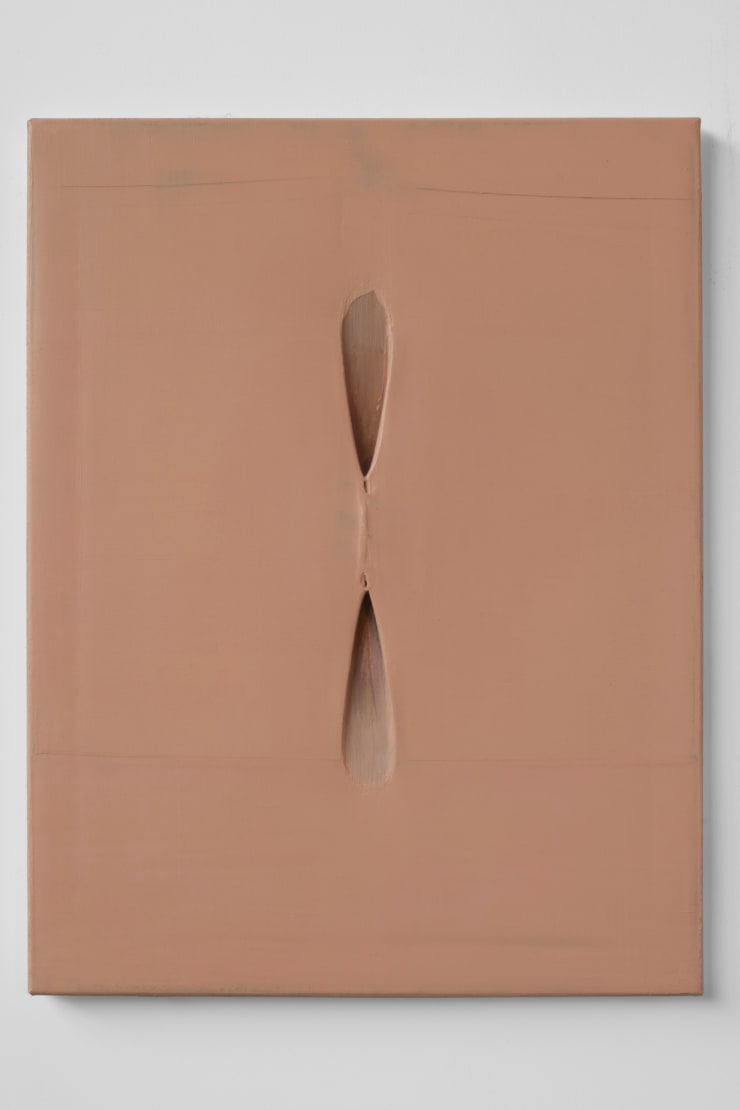

Themes of imminence and intangibility are present throughout Eli's practice. In 2016, he began making a series of small bronze, wall-mounted reliefs that resemble wounds stitched together, puckering and pulling apart at the seams.

Though more abject, his ability to inject pulsing life into otherwise inert material recalls the apotheosis of The Kiss––when the pads of fingertips appear to press into a thigh, and cold stone turns to flesh. The taut skin-like surfaces of these reliefs were achieved by shrink-wrapping plastic around stretcher bars until the heated, viscous material contracted in a way that caused the melting film to stick together and stretch. At first, the result reminded him of belly buttons and anuses. Later, a friend pointed out that they looked like the maternal body approaching childbirth.

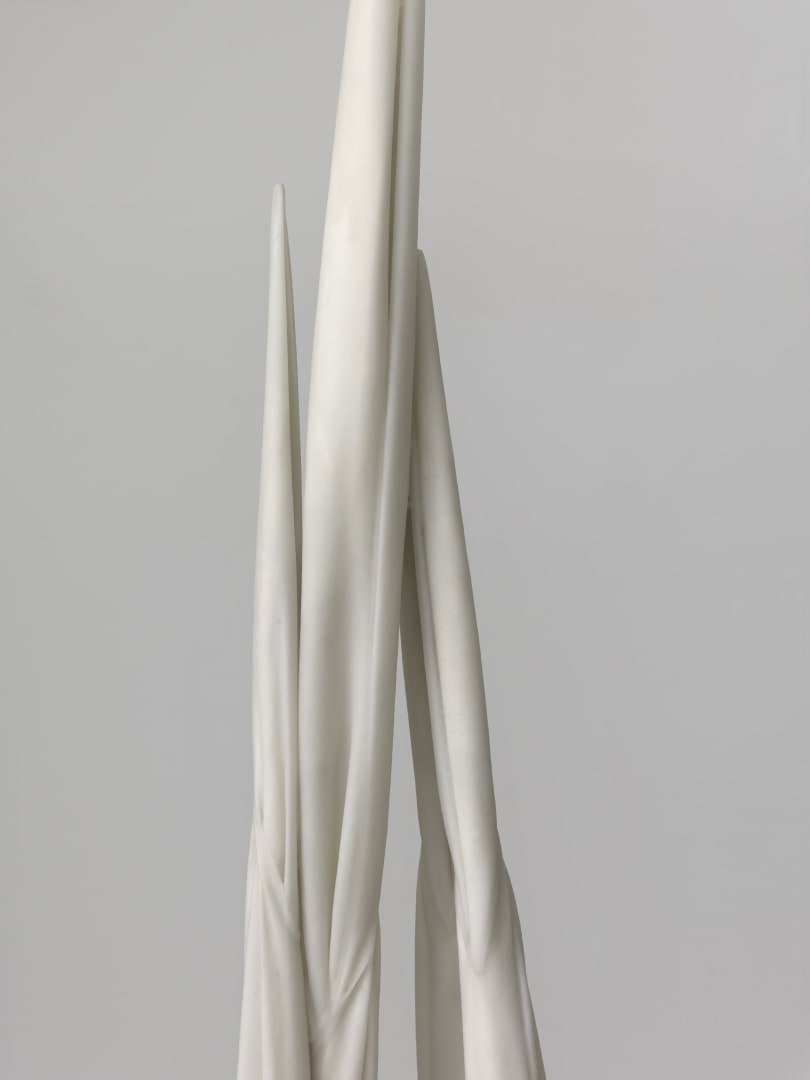

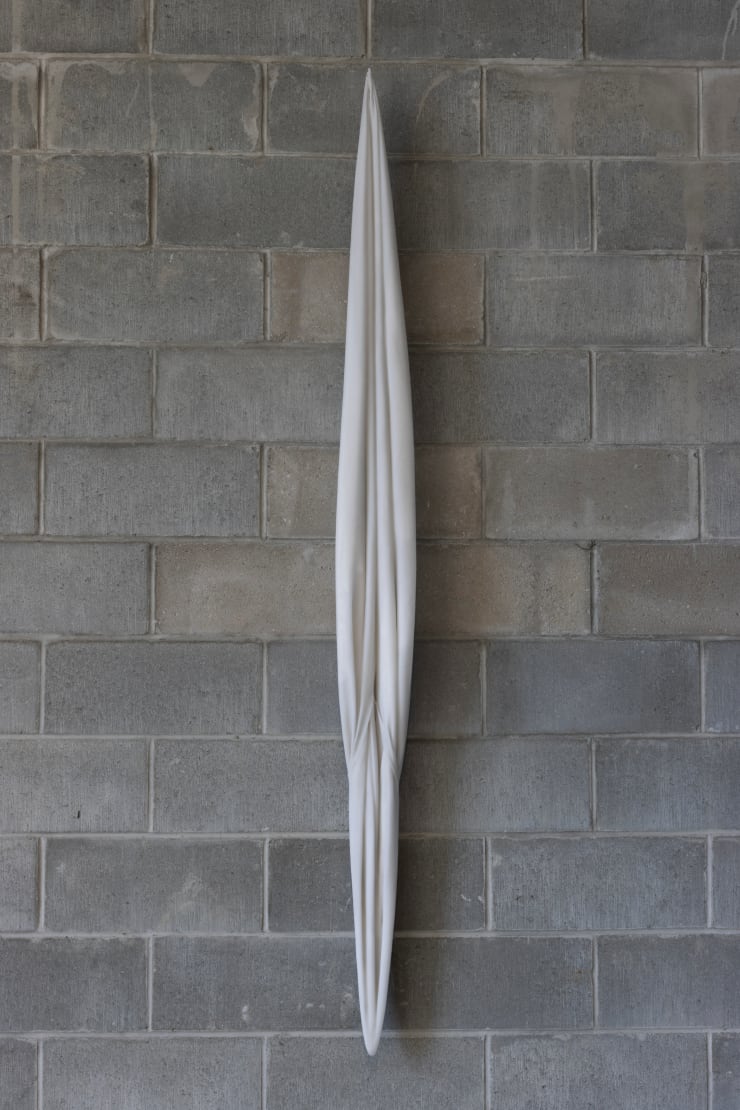

His show at Ramiken in 2021 introduced more frozen gestures with a new sense of weightlessness and Gothic verticality. Using canvas instead of bronze, Eli folded the illusion of laceration into a new series of paintings. “Their form embodies a legible record of the time and process of their making in a manner that casting doesn’t.” Recurring themes like pulling and stretching, the abject and the pristine, the pulsing and the preserved––also gelled into larger forms. The "Motes," created by pouring resin over canvas hung from the ceiling, were born from the desire to convey something "more expansive that burst out of the frame...a physical sensation…like a loud sound." The suspension of the hanging cloth and the impression of "vertical motion" make "the forms feel torn between gravity and ascending force."[2] Human-scale and labial, alien and evocative, they appeal to a physical and psychological state. Sanded to perfection, the draped surface of the "Motes," as well as the series to follow, recall the creamy-white ivory of bone. Like Constantin Brancusi's Sleeping Muse, they are hard avatars of soft forms.

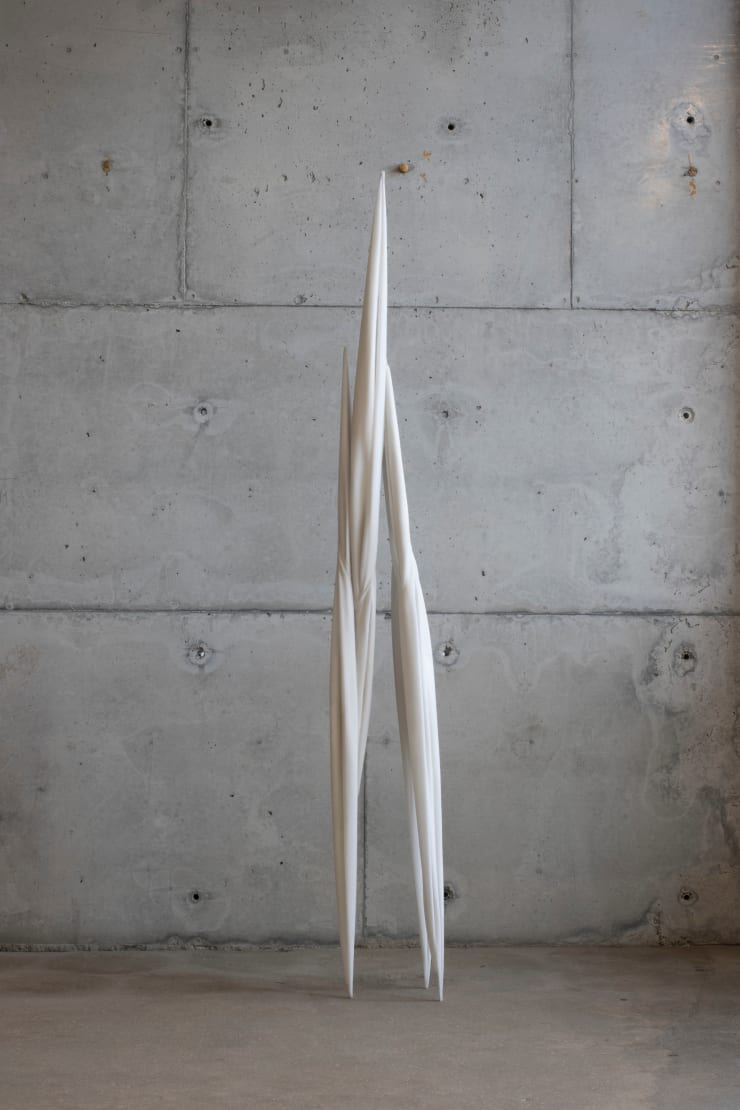

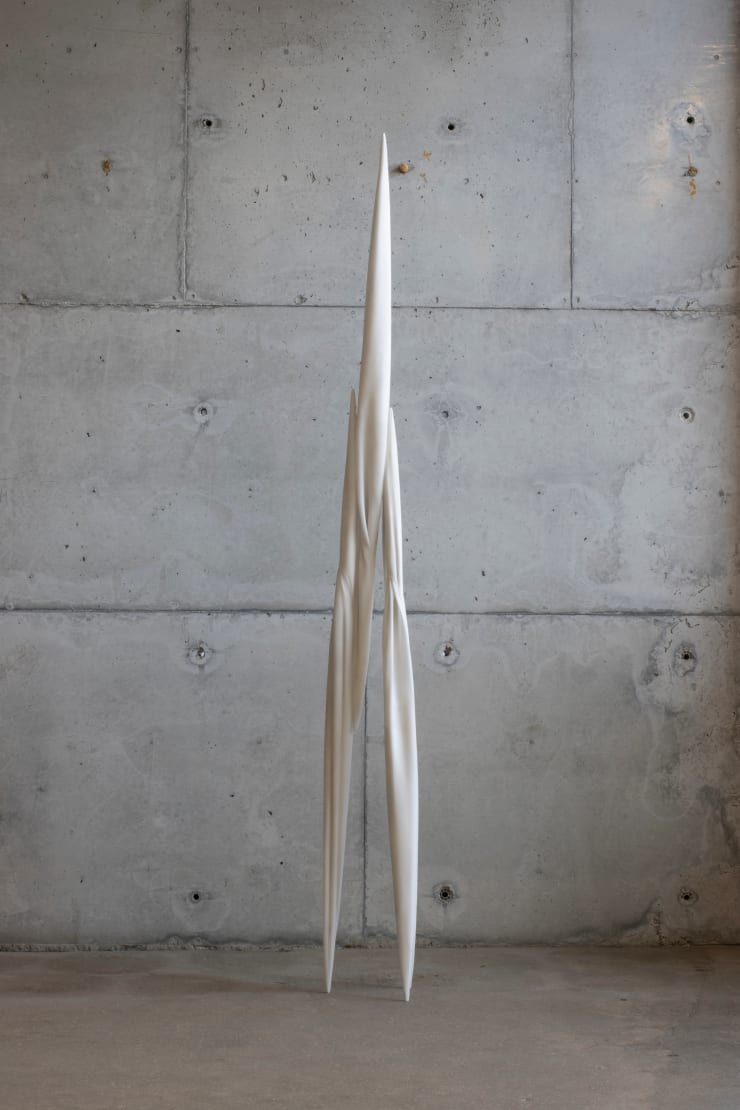

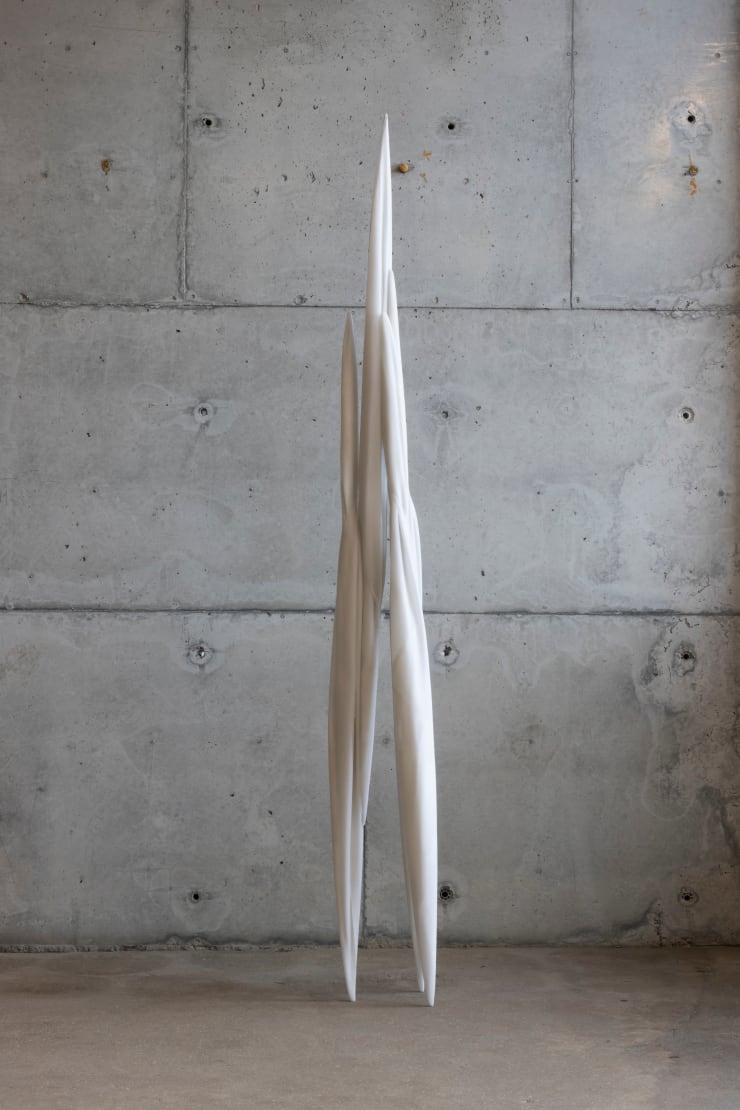

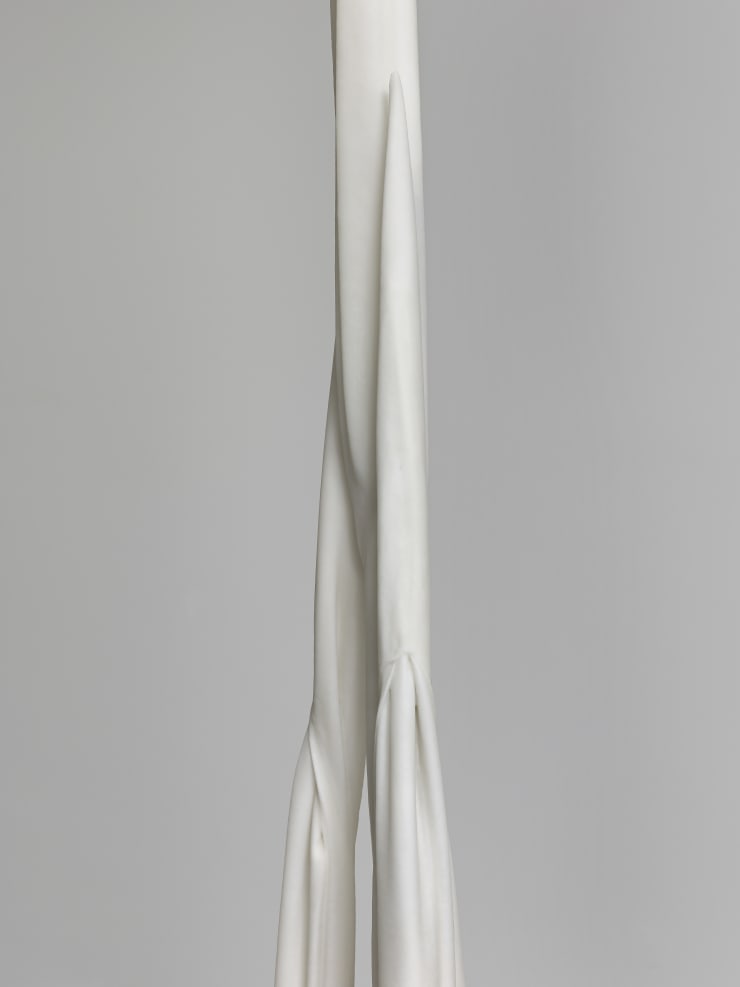

The "Monocarps," named after a plant that only flowers once before dying, was about transcending the base of the wall––or as he puts it, "unpinning the butterfly." Like Alberto Giacometti, these upright, freestanding sculptures address the viewer. Entirely freed from auxiliary support, they appear to be walking toward you. Like Louise Bourgeois' Maman, they stage a dynamic encounter between the object and the mind: they appear as if they might devour you. While Eli's work has formal affinities with artists as diverse as Giacometti, Benglis, or even Brancusi, it so clearly has other origins that provide the aura to these forms. Comparisons like these are far less interesting than the strangeness of the human experience, accessible to us all.

Eli describes his process through the lens of anticipation: "When I start closing in on something in the world that I'm going to make," he told me, "I start to feel it and almost see it." Like a shadow, the thing will appear peripherally. "I unconsciously start putting my hands out to feel its contours."

–– Lola Kramer

-

Eli PingMonocarp 1, 2022cotton and resin226 x 30 x 20 cm

Eli PingMonocarp 1, 2022cotton and resin226 x 30 x 20 cm

89 x 11 3/4 x 7 7/8 in -

Eli PingMonocarp 2, 2022cotton and resin238 x 32 x 20 cm

Eli PingMonocarp 2, 2022cotton and resin238 x 32 x 20 cm

93 3/4 x 12 5/8 x 7 7/8 in -

Eli PingMonocarp 3, 2022cotton and resin243 x 31 x 23 cm

Eli PingMonocarp 3, 2022cotton and resin243 x 31 x 23 cm

95 5/8 x 12 1/4 x 9 1/8 in -

Eli PingMote 1, 2022cotton and resin195 x 16 x 12 cm

Eli PingMote 1, 2022cotton and resin195 x 16 x 12 cm

76 3/4 x 6 1/4 x 4 3/4 in -

Eli PingMote 2, 2022cotton and resin200 x 17 x 13 cm

Eli PingMote 2, 2022cotton and resin200 x 17 x 13 cm

78 3/4 x 6 3/4 x 5 1/8 in -

Eli PingMote 3, 2022cotton and resin167 x 18 x 10 cm

Eli PingMote 3, 2022cotton and resin167 x 18 x 10 cm

65 3/4 x 7 1/8 x 4 in -

Eli PingUntitled , 2022Oil on canvas, thread65 x 48 cm

Eli PingUntitled , 2022Oil on canvas, thread65 x 48 cm

25 5/8 x 18 7/8 in

-

Eli PingUntitled, 2022Oil on canvas, thread65 x 48 cm

Eli PingUntitled, 2022Oil on canvas, thread65 x 48 cm

25 5/8 x 18 7/8 in -

Eli PingUntitled, 2022Oil on canvas, thread40 x 30 cm

Eli PingUntitled, 2022Oil on canvas, thread40 x 30 cm

15 3/4 x 11 3/4 in